The History of the Iron Ore Company of Canada

The history of the Iron Ore Company of Canada (IOC) is effectively the biography of Labrador West. It is one of the most successful—and politically complex—industrial projects in Canadian history. Founded in 1949, IOC was created not just to mine ore, but to build an empire in the wilderness. It built towns, railways, and ports where nothing existed before.

The Founding: “Operation Civilization” (1949–1954)

Following A.P. Low’s discovery of iron ore in the 1890s, the region sat untouched for 50 years due to its remoteness. However, the post-WWII boom saw American steel mills running low on domestic iron ore, prompting them to look north.

- The Consortium (1949): IOC formed as a partnership between the Canadian mining firm Hollinger and powerful American steel companies, led by the M.A. Hanna Company of Cleveland. This partnership guaranteed a market for whatever IOC mined.

- The Impossible Railway (1950–1954): Before any ore could be sold, IOC had to build the Quebec North Shore and Labrador Railway (QNS&L). Costing nearly $300 million (billions today), it required the largest civilian airlift in history (at it’s time) to fly heavy machinery into the wilderness to build the tracks from both north and south simultaneously.

- The First Mine: Operations began at Knob Lake (Schefferville) in 1954. The ore here was “Direct Shipping Ore”—high-grade rock that could be dug up and thrown directly into a furnace.

The Political Architect: Smallwood’s Grand Design

The industrial explosion of Labrador West cannot be separated from the political ambition of Joey Smallwood, the first Premier of Newfoundland. When Newfoundland joined Confederation in 1949, the interior of Labrador was essentially a dormant asset. Smallwood viewed the massive iron deposits not just as a mine, but as the economic engine that would justify the new province’s existence.

The “Newfoundland First” Mandate – Smallwood granted IOC incredible concessions—including vast land rights and tax breaks—to get the project moving. However, he demanded one non-negotiable in return: jobs for Newfoundlanders.

Because the QNS&L railway originated in Sept-Îles, Quebec, it was logistically easier to hire workers from Quebec. Smallwood fought fiercely to prevent Labrador City from becoming a “satellite of Quebec.”

He forced the companies to adhere to a “preference clause” for Newfoundland labor. This led to aggressive recruitment drives in the island’s outports, flying thousands of fishermen north to become miners, ensuring the benefits of the resource flowed back to the province.

The symbiotic relationship between the Premier and the Company was cemented in stone. When the operations officially commenced in 1962, Smallwood himself detonated the inaugural blast. In recognition of his role in unlocking the region, IOC named its flagship operation the Smallwood Mine.

The Strategic Pivot: The Carol Project (1960s)

By the late 1950s, the steel industry evolved. Furnaces began demanding “pellets” (processed concentrate) rather than raw rock. IOC realized its future lay further south in Labrador City.

In 1958, IOC announced the Carol Project, leading to the opening of the Smallwood Mine in 1962.

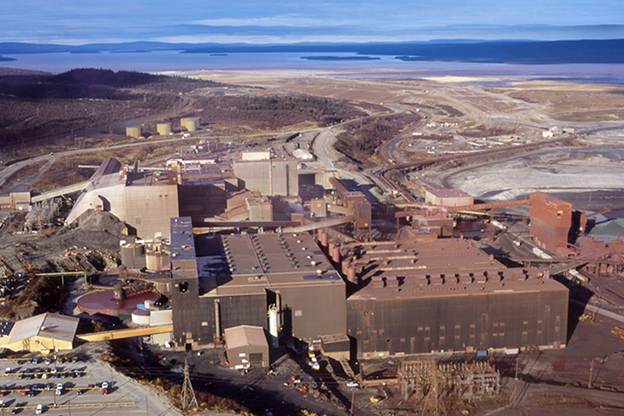

- The Technology: The ore here was low grade (38%), but IOC invested in new technology (Humphreys Spirals) to upgrade it to 66% concentrate on-site. This transformed Labrador City into a “factory” town rather than just a mine site.

- The Town: Unlike the temporary camps of the past, IOC designed Labrador City as a modern suburb to attract families, signaling a permanent commitment to the region.

The Corporate Crisis & The Closure (1980s)

The early 1980s marked the company’s darkest chapter. Global demand for steel collapsed, forcing IOC to choose between saving Schefferville or Labrador City.

The Mulroney Era (1977–1983)

This period serves as the origin story for Canada’s 18th Prime Minister, Brian Mulroney. Hired as President in 1977, Mulroney was a slick labour lawyer from Quebec known for his “golden throat.” His mandate was to bring labour peace to a company plagued by strikes. He brought a sense of glamour to the role, operating out of a corporate jet and drinking beer with union bosses.

However, the 1981–1982 crisis forced his hand. With the company losing millions, the American owners issued an ultimatum: cut the losses or face bankruptcy.

The “Black Day”: November 2, 1982

Mulroney made the decision to permanently close the Schefferville operations. It was a death sentence for the town of 4,000 people. Almost overnight, schools and arenas emptied, and houses were sold for $1.00 or bulldozed to avoid taxes.

Mulroney spun this corporate ruthlessness into a political asset during his 1983 leadership bid. He negotiated a massive $9 million severance package for the workers, arguing that while he had to make the tough decision to save the company, he treated the men with dignity—something a “soulless American manager” would not have done.

For Labrador City, the legacy is mixed. Mulroney is viewed as a savior who cut Schefferville loose to save the Carol Project, but also as the man who taught residents a chilling lesson: if the numbers don’t work, the company will erase you.

The Rio Tinto Era (2000–Present)

In 2000, the global mining giant Rio Tinto acquired a majority stake in IOC, integrating Labrador West into a massive global network. The ownership structure now includes Rio Tinto (~58.7%), Mitsubishi Corporation (~26.2%), and the Labrador Iron Ore Royalty Corp (~15.1%).

The Future Frontier: Electrification and Automation (2020s–Present)

While the history of IOC is defined by massive diesel machinery and physical labor, its future is being written in code and electricity. The company has implemented several advanced technologies at its Labrador City operations, specifically targeting electrification, automation, and decarbonization to meet its 2050 net-zero goals.

The “Ghost” Train: North America’s Hidden Electric Railway Unknown to many, IOC operates one of the last remaining fully electric cargo railways in North America. However, this is distinct from the main QNS&L line that travels to Sept-Îles.

- The Autonomous Loop: Within the mine itself, a specialized 13-km fully electric railway transports raw ore from the mine pit to the processing plant (concentrator).

- The Tech: It utilizes GMD SW1200MG electric locomotives that run on electricity delivered via overhead catenary wires.

- Automation: Crucially, these trains are unmanned. They operate on an automatic block system, advancing section-by-section based on track clearance without a human operator in the cab.

Modernizing the Main Line (QNS&L) While the main 418 km railway to the port remains diesel-electric, it has been heavily modernized.

- Locotrol: IOC uses distributed power technology, placing locomotives in the middle of the 2.5 km long trains. These are controlled remotely from the front cab, preventing the massive trains from snapping under their own weight.

- Laser Inspection: The tracks are monitored by high-speed laser and optical geometry cars (supplied by MERMEC) that scan the rails for defects while moving at speed, replacing the old manual inspections.

Robots in the Pit: Autonomous Vehicles The era of the operator sitting in a freezing cab is ending. IOC is a leader in deploying electric heavy machinery to improve safety and efficiency.

- Autonomous Drills: In a pilot project with FLANDERS, IOC has deployed autonomous electric blasthole drills (converted P&H 320XPC models). These machines are all-electric (plug-in) and are controlled remotely from a warm office, removing operators from the dangerous pit environment.

- Future Haulage: While the massive fleet of Komatsu and Caterpillar haul trucks remains diesel-powered for now, Rio Tinto is actively exploring methods to repower these trucks with renewable sources.

The “Green Steel” Pivot: Decarbonization A major operational focus is replacing heavy fuel oil (Bunker C) with clean electricity in the processing plants to produce “Green Steel” components.

- The Electric Boiler: IOC is installing a 40-megawatt electric boiler to generate steam for the concentrate and pellet plants. This replaces old heavy fuel oil boilers, drastically cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

- Plasma Torches: The company is piloting plasma torch technology in its pellet induration machines. This technology uses electricity to generate the extreme heat needed to bake iron ore pellets, aiming to eliminate the fossil fuels currently used in the furnaces.

- High-Grade Pellets: IOC now produces specific high-purity pellets designed for Direct Reduction (DR) steelmaking—a modern method that uses hydrogen instead of coal, requiring the exceptionally high-quality ore that Labrador City provides.