The History of Wabush Mines

The story of Wabush Mines is the story of the “Little Brother” that fought to survive. While the Iron Ore Company of Canada (IOC) was the giant down the road in Labrador City, Wabush Mines was smaller, scrappier, and technically more complex. Its history is defined by a specific chemical flaw in the rock—Manganese—which eventually killed the mine, only for new technology to bring it back to life.

The Beginning: The Consortium (1950s–1965)

While IOC was a single massive corporation, Wabush Mines was born as a consortium. In the 1950s, several smaller American and Canadian steel companies, who preferred not to buy from their competitor IOC, banded together to secure their own supply.

The Manager: The operation was managed by Pickands Mather & Co. out of Cleveland, Ohio.

The Partners: The ownership group included Canadian giants Stelco and Dofasco from Hamilton, alongside American firms like Inland Steel.

The Construction (1961–1965): The consortium built the Scully Mine, named after V.W. Scully, the president of Stelco.

The Town: Because Labrador City was strictly an “IOC Town,” the partners built their own town next door: Wabush.

Unlike IOC, which built a massive railway infrastructure from scratch, Wabush Mines had to be strategic. Instead of building a line all the way to the ocean, they built a short spur line known as the Wabush Lake Railway to connect to IOC’s QNS&L railway, paying IOC to transport their ore to the coast.

The “Manganese” Curse

From day one, Wabush Mines had a geological problem: the iron ore in the Scully pit contained high levels of Manganese. In small amounts, manganese is acceptable, but if the concentration is too high, it damages the blast furnaces used to make steel.

For 50 years, the engineers at Wabush were constantly fighting to blend the ore to keep the manganese levels low enough to sell. It was a constant handicap that made their production costs higher than IOC’s. Unlike IOC, which centralized operations in Labrador City, Wabush Mines was a split operation. The Scully Mine in Wabush dug the rock and crushed it into “Concentrate” powder. This powder was shipped south by rail to Pointe Noire in Sept-Îles Quebec, where a separate Pellet Plant turned the powder into pellets before shipping.

The Cliffs Era: Boom and Bust (2007–2014)

In 2007, the disjointed ownership group sold the mine to Cliffs Natural Resources, a massive American mining firm. This marked the beginning of the end for the “Old Era”.

Cliffs took over during the “Supercycle” when iron ore prices soared to over $150 per tonne. They ran the mine hard. Because prices were so high, Cliffs didn’t worry about efficiency. The Scully Mine became one of the highest-cost operations in North America as they spent huge amounts of money pumping water out of the deep pits and managing the manganese.

The crash came between 2013 and 2014. When iron ore prices collapsed to $90 and then $50, the math broke. It cost Cliffs more to mine the rock than they could sell it for.

The Trauma: The 2014 Closure

On February 11, 2014, Cliffs announced the absolute closure of Wabush Mines. The impact was immediate and devastating:

The Shutdown: 500 high-paying jobs vanished instantly.

The Betrayal: Cliffs filed for creditor protection under the CCAA (bankruptcy protection for its Canadian division).

The Pension Cut: In a move that enraged the province, Cliffs cut the pensions of retirees by roughly 21–25% and eliminated health benefits.

The “Orphaned” Mine: Cliffs walked away, turning off the pumps. The pit began to flood; if the water rose too high, the mine would be ruined forever.

A small group of local engineers and the union maintained a vigil, keeping the pumps running on a skeleton budget and praying a buyer would be found before the water destroyed the equipment.

The Sears/Wabush Effect: A Legal Legacy

The story of Wabush Mines is often cited as a warning about foreign ownership. The financial devastation of the Wabush miners in 2014 served as the warning shot for the national collapse of Sears Canada in 2017, leading to the “Sears/Wabush Effect”.

This phenomenon highlighted a glaring loophole in Canadian bankruptcy law (the CCAA) that allowed corporations to legally raid the deferred wages of their retirees to pay off banks and investors. Under the old rules, if a company had an “Underfunded Pension Plan,” that deficit was treated as an unsecured debt, meaning the money simply vanished after secured creditors like banks were paid.

The Fight for Deferred Wages Retirees argued that a pension is not a “benefit” but a “deferred wage”—money workers accepted in lieu of higher hourly pay, which was now being stolen to pay banks. The Wabush Pensioners Committee joined forces with national organizations to shame the government into action.

This pressure eventually led to the Pension Protection Act (Bill C-228), which received Royal Assent in April 2023. The law fundamentally altered Canada’s bankruptcy laws by giving pensions “Super Priority,” ensuring they are paid before secured creditors.

However, for Wabush, it was a bitter irony. The law is not retroactive. The Wabush Mines retirees did not get their money back; they remain on reduced pensions, having won the war for future Canadian workers while losing their own battle.

The Resurrection: Tacora Resources (2017–Present)

Just when the town had given up hope, a new player arrived. Tacora Resources, a company formed specifically to save this mine, bought the assets in 2017.

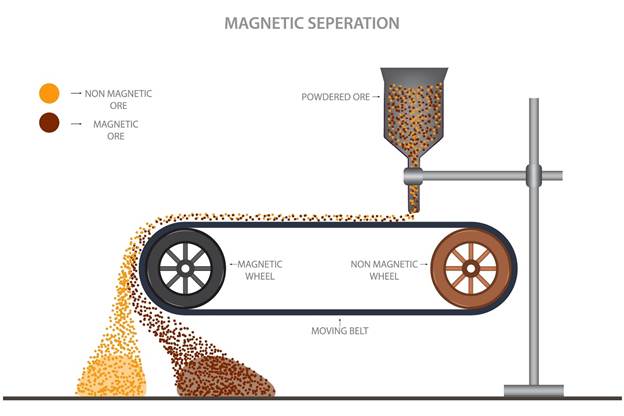

Tacora’s strategy relied on a “Secret Sauce”: new technology. They didn’t just restart the mine; they fixed the flaw by installing Manganese Reduction Circuits using specialized high-intensity magnetic separators. This technology allowed them to remove the manganese that had plagued the mine for 50 years, creating a higher-grade, “cleaner” product.

In the summer of 2019, the Scully Mine roared back to life. Today, the mine is fully operational, shipping its concentrate via the railway to Sept-Îles for markets in Europe and Asia.